Introduction

Back in 2015 I published an article [1] about the QR decomposition of a centrosymmetric real matrix. In 2016 I started thinking about the meaning of this decomposition and centrosymmetric matrices in general. I discovered that centrosymmetric matrices have a natural interpretation as split-complex matrices and even more, that the centrosymmetric QR decomposition of a matrix actually corresponds to a QR decompositon of a split-complex matrix for which the original matrix is it representation. In a certain sense, the centrosymmetric QR decomposition introduced in [1] of a real square matrix of order  is equivalent to a QR decomposition of a corresponding split-complex square matrix of order

is equivalent to a QR decomposition of a corresponding split-complex square matrix of order  . All these notions will be made precise in the following sections. This blog post is based on my own preprint.

. All these notions will be made precise in the following sections. This blog post is based on my own preprint.

Matrix representations

If  is a finite-dimensional vector space then we denote by

is a finite-dimensional vector space then we denote by  the set of all linear transformations

the set of all linear transformations  . Recall that if

. Recall that if  is an

is an  -dimensional vector space and

-dimensional vector space and  an ordered basis for

an ordered basis for  , then every linear transformation

, then every linear transformation  has an

has an  matrix representation with respect to

matrix representation with respect to  denoted

denoted ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [T]_\mathcal{B}](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9681ac63ba28fe01a34082b913969eed_l3.png) . Further, for any two linear transformations

. Further, for any two linear transformations  we have

we have ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [S \circ T]_\mathcal{B} = [S]_\mathcal{B} [T]_\mathcal{B}](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f8a34a6154bbdcbec92f422ac7a4f5bb_l3.png) . The standard ordered basis for

. The standard ordered basis for  i.e. the basis

i.e. the basis  is defined as

is defined as  if

if  and

and  otherwise.

otherwise.

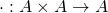

An algebra  is an ordered pair

is an ordered pair  such that

such that  is a vector space over a field

is a vector space over a field  and

and  is a bilinear mapping called multiplication.

is a bilinear mapping called multiplication.

Let  be an algebra. A representation of

be an algebra. A representation of  over a vector space

over a vector space  is a map

is a map  such that

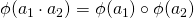

such that

for all

for all  .

.

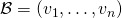

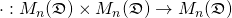

Let  denote the set of

denote the set of  real matrices. If

real matrices. If  is an

is an  -dimensional vector space and

-dimensional vector space and  an ordered basis for

an ordered basis for  then every linear transformation

then every linear transformation  has a matrix representation

has a matrix representation ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [T]_\mathcal{B} \in M_n(\mathbb{R})](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5791b83f990fe4853f18a333a6ddcad3_l3.png) . For each

. For each  we have

we have  . Since

. Since  is

is  -dimensional, we have and ordered basis

-dimensional, we have and ordered basis  and

and ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com [\phi(a)]_\mathcal{B} \in M_n(\mathbb{R})](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-cef0b0493a1932fe8a0bc57934c16081_l3.png) . A matrix representation of

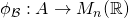

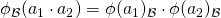

. A matrix representation of  with respect to

with respect to  } is a map

} is a map  such that

such that ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \phi_\mathcal{B}(a) = [\phi(a)]_\mathcal{B}](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0c7f8d77f75011bb6e57fc5e5e1f4d25_l3.png) for all

for all  . Further, we have

. Further, we have  for all

for all  . These are all well known notions from representation theory, for further information, one can consult one of the standard textbooks, for example see [3].

. These are all well known notions from representation theory, for further information, one can consult one of the standard textbooks, for example see [3].

Algebra of split-complex numbers

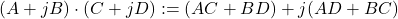

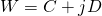

Let  , where

, where  is given by

is given by

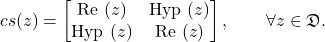

(1)

for all

. It is straightforward to verify that

is

an algebra. This is the well known algebra of

split-complex numbers. The split-complex numbers are also sometimes known as

hyperbolic numbers.

Similarly as for the complex numbers, each real number

can be identified with the pair

.

With this correspondence, the pair

has the property

and

. Due to this property,

is called the

hyperbolic unit.

Since

, in the following we shall denote a pair

simply with

. The

conjugate of

is defined as

.

For a hyperbolic number  we define the real part as

we define the real part as  and hyperbolic part as

and hyperbolic part as  .

.

For the module we set  and we have

and we have  for all

for all  .

.

For an extensive overview of the theory of hyperbolic numbers as well of their usefulness in Physics one can check the literature, for example [2]. For the rest of this blog post, we shall refer to these numbers as split-complex numbers.

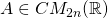

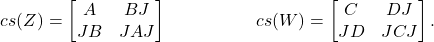

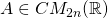

Centrosymmetric representation of split-complex matrices

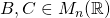

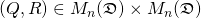

By  we denote the set of all

we denote the set of all  split-complex matrices i.e. matrices in which entries are split-complex numbers. Note that

split-complex matrices i.e. matrices in which entries are split-complex numbers. Note that  if and only if there exist

if and only if there exist  real matrices

real matrices  ,

,  such that

such that  . If

. If  is a matrix then its transpose is defined as

is a matrix then its transpose is defined as  for all

for all  and is denoted with

and is denoted with  . In the following we denote by

. In the following we denote by  the

the  identity matrix and by

identity matrix and by  the

the  zero matrix. Let

zero matrix. Let  be defined as

be defined as  for each

for each  . Note that

. Note that  . A matrix

. A matrix  is upper-triangular if

is upper-triangular if  for all

for all  .

.

A real matrix  is centrosymmetric if

is centrosymmetric if  . An overview of centrosymmetric matrices can be found in [4]. We denote by

. An overview of centrosymmetric matrices can be found in [4]. We denote by  the set of all

the set of all  centrosymmetric real matrices.

centrosymmetric real matrices.

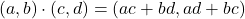

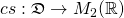

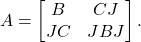

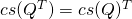

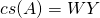

For the algebra  of split-complex numbers the well-known matrix representation

of split-complex numbers the well-known matrix representation  with respect to

with respect to  is given by

is given by

(2)

It is straightforward to check that for all

we have

.

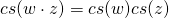

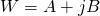

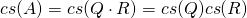

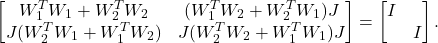

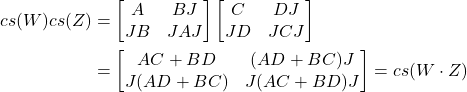

Further, on the vector space  there is a natural multiplication operation

there is a natural multiplication operation  given by

given by

(3)

for all

. It is easy to verify that

is an algebra. In the following we refer to this algebra as the

algebra of split-complex (square) matrices and denote it with

.

Note that in the following whenever we have two matrices  , their product shall explicitly be written with a dot '

, their product shall explicitly be written with a dot ' ', e.g.

', e.g.  to indicate multiplication defined in (3). Otherwise, if

to indicate multiplication defined in (3). Otherwise, if  we simply write

we simply write  .

.

To state and prove our main result, we shall need the following well known characterization of centrosymmetric matrices.

Proposition 1:

Let  . Then

. Then  if and only if there exist

if and only if there exist  such that

such that

(4)

Proof:

Suppose

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[A =\begin{bmatrix}X & Y \\W & Z\end{bmatrix}.\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-dfc22a1c4d521ab6264a5e940d168b8b_l3.png)

Since

is centrosymmetric, we have

, or equivalently, in block-form

*** QuickLaTeX cannot compile formula:

\[\begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}X & Y \\W & Z\end{bmatrix} =\begin{bmatrix}X & Y \\W & Z\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

*** Error message:

\begin{bmatrix} on input line 17 ended by \end{equation*}.

leading text: ...begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

Missing $ inserted.

leading text: ...begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

Missing } inserted.

leading text: ...begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

Missing \cr inserted.

leading text: ...begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

Missing $ inserted.

leading text: ...begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

Missing } inserted.

leading text: ...begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

Missing \right. inserted.

leading text: ...begin{bmatrix}\ & J \\J & \\end{bmatrix}\]

Improper \prevdepth.

leading text: \end{document}

Missing $ inserted.

leading text: \end{document}

Missing } inserted.

leading text: \end{document}

This is equivalent to

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{bmatrix}JW & JZ \\JX & JY\\end{bmatrix} =\begin{bmatrix}YJ & XJ \\ZJ & WJ\end{bmatrix}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-dd5627f494d4bca7581085523a98716c_l3.png)

We now have

and

, so

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[A = \begin{bmatrix}X & JWJ \\W & JXJ\end{bmatrix}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7c3957443d30be0edce1f4d5805ced92_l3.png)

Now, by choosing

and

and from the fact

it follows that

has the form (4).

Conversely, suppose  has the form (4). It can easily be shown by block-matrix multiplication that

has the form (4). It can easily be shown by block-matrix multiplication that  , hence

, hence  is centrosymmetric.

is centrosymmetric.

QED.

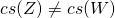

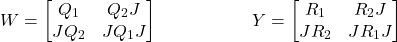

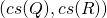

The map  defined as

defined as

(5)

is a matrix representation of

. We call the representation

the

standard centrosymmetric matrix representation of

.

Proof:

Let  and

and  be such that

be such that  and

and  .

.

We now have

which proves the claim.

QED.

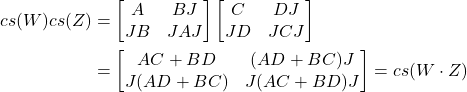

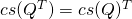

Proposition.

Let  . Then

. Then  .

.

Proof.

Let  . Then

. Then

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[{cs}(Q^T) = {cs}(A^T + jB^T) = \begin{bmatrix}A^T & B^T J \\J B^T & J A^T J\end{bmatrix}.\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-50052d6274db4c924f8f8c3e0721d654_l3.png)

On the other hand, keeping in mind that

we have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[{cs}(Q)^T = \begin{bmatrix}A & B J \\J B & JAJ\end{bmatrix}^T =\begin{bmatrix}A^T & (JB)^T \\(BJ)^T & (JAJ)^T\end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix}A^T & B^T J \\J B^T & J A^T J\end{bmatrix}.\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-9714f4b56d03557826eb2b0e6f887b47_l3.png)

Hence,

.

QED.

Proposition.

The map  is a bijection.

is a bijection.

Proof.

Injectivity. Let  and

and  and

and  . From this,

. From this,

it follows that  or

or  . Assume that

. Assume that  . Then

. Then

Since

we have

. Let now

and assume that

. Then from

it follows

. Now multiplying

with

from the left implies

, which is a contradiction.

We conclude that

is injective.

Surjectivity. Let  . By proposition 1 we can find matrices

. By proposition 1 we can find matrices  and

and  such that (4) holds. But then

such that (4) holds. But then  and since

and since  was arbitrary, we conclude that

was arbitrary, we conclude that  is surjective.

is surjective.

Now, injectivity and surjectivity of  imply by definition that

imply by definition that  is a bijection.

is a bijection.

QED.

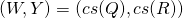

Correspondence of QR decompositions

Definition:

Let  . A pair

. A pair  with

with  is a QR decomposition of

is a QR decomposition of  over

over  if the following holds:

if the following holds:

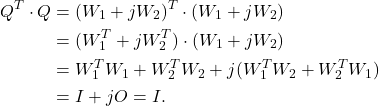

is orthogonal, i.e.

is orthogonal, i.e.  ,

, is upper-triangular,

is upper-triangular,

The notion of a  double-cone matrix was introduced by the author in [1].

double-cone matrix was introduced by the author in [1].

Here we state the definition in block-form for the case of  .

.

Definition:

Let  . Then

. Then  is a double-cone matrix iff there exist

is a double-cone matrix iff there exist  both upper-triangular such that

both upper-triangular such that

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[H = \begin{bmatrix}A & BJ \\JB & JAJ\end{bmatrix}.\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-808405c728b3915d63f5080e9576518b_l3.png)

Definition:

Let  . A pair

. A pair  , with

, with  is a centrosymmetric QR decomposition of

is a centrosymmetric QR decomposition of  if the following holds:

if the following holds:

is orthogonal matrix,

is orthogonal matrix, is double-cone matrix,

is double-cone matrix,

The algorithm to obtain an approximation of a centrosymmetric QR decomposition of a given centrosymmetric matrix  was given in [1].

was given in [1].

The following theorem provides one interpretation of the centrosymmetric QR decomposition, in the case of square centrosymmetric matrices of even order by establishing the equivalence of their centrosymmetric QR decomposition with the QR decomposition of the corresponding split-complex matrix.

Theorem 1 (QR decomposition correspondence):

Let  . Then

. Then  is a QR decomposition of

is a QR decomposition of  if and only if

if and only if

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[(\CsEmb{Q}, \CsEmb{R}) \in \CsMat{2n} \times \CsMat{2n}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e9a458e3f996c705150a04da9762d369_l3.png)

is a centrosymmetric QR decomposition of

.

Proof.

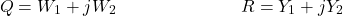

Let  be a QR decomposition of

be a QR decomposition of  .

.

Let  and

and  . We have

. We have

Since

it follows that

.

From this we have

i.e.

hence

is orthogonal. Since

is upper-triangular and

, then by definition we have that both

and

are upper-triangular. Further,

is centrosymmetric by definition. From this it follows that

is centrosymmetric double-cone.

Finally, we have

. Hence,

is

a centrosymmetric QR decomposition of

.

Conversely, let  . If

. If  is a centrosymmetric QR decomposition of

is a centrosymmetric QR decomposition of  then

then  where

where  is centrosymmetric and orthogonal and

is centrosymmetric and orthogonal and  is a double-cone matrix.

is a double-cone matrix.

From the fact that  is centrosymmetric we have (by Proposition 1) that

is centrosymmetric we have (by Proposition 1) that

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[W = \begin{bmatrix}W_1 & W_2 J \\J W_2 & J W_1 J\end{bmatrix}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-c10ff9bad6cc022b85b4befe7f99a024_l3.png)

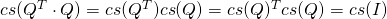

Now the property of

being orthogonal i.e. the condition

implies

(6)

On the other hand, we have

(7)

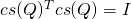

First we prove that

is orthogonal. From (6) we obtain

The matrix

is centrosymmetric and double-cone which implies

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Y = \begin{bmatrix}Y_1 & Y_2 J \\J Y_2 & J Y_1 J\end{bmatrix}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5788a9be2737c3666186cb5481c37365_l3.png)

where both

and

are upper-triangular. This now implies that

is upper-triangular.

Finally, let us prove that  . We have

. We have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[Q \cdot R = {cs}^{-1} (W) {cs}^{-1} (Y) = {cs}^{-1}(WY) = {cs}^{-1}(\CsEmb{A}) = A.\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-dd022056b2f5c502b64e158d2a87d15e_l3.png)

We conclude that

is a QR decomposition of

.

QED.

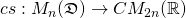

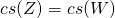

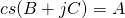

Example:

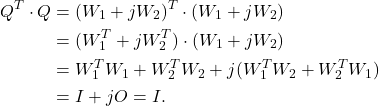

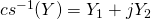

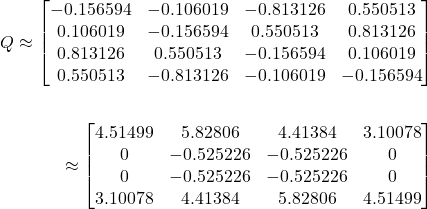

Let

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[A = \begin{bmatrix}1 + 2j & 2 + 3j \\3 + 4j & 4 + 5j\end{bmatrix}.\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-db6205a4ba7d1af37703a787ba0df9c9_l3.png)

Note that

where

(8)

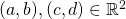

We have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[{cs}(A) = {cs}(W + jZ) = \begin{bmatrix}W & ZJ \\JZ & JWJ\end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix}1 & 2 & 3 & 2 \\3 & 4 & 5 & 4 \\4 & 5 & 4 & 3 \\2 & 3 & 2 & 1\end{bmatrix}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-1c69ab9d656b5f8fe677e72f6445a893_l3.png)

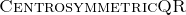

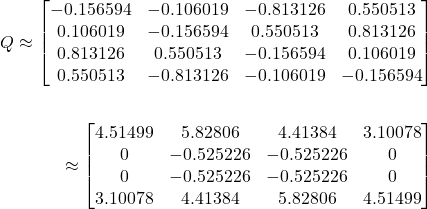

By applying the

algorithm from [1] to

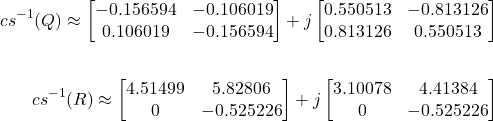

we obtain the approximations:

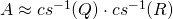

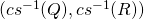

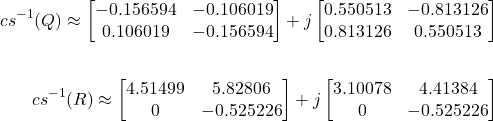

Applying  to

to  and

and  yields:

yields:

with

. Now, from Theorem 1 we conclude that

is an approximation of a QR decomposition of

.

Conclusion

We introduced the standard centrosymmetric representation  for split-complex matrices. Using this representation we proved that a QR decomposition of a square split-complex matrix

for split-complex matrices. Using this representation we proved that a QR decomposition of a square split-complex matrix  can be obtained by calculating the centrosymmetric QR decomposition introduced by the author in [1] of its centrosymmetric matrix representation

can be obtained by calculating the centrosymmetric QR decomposition introduced by the author in [1] of its centrosymmetric matrix representation  .

.

References

- Burnik, Konrad. A structure-preserving QR factorization for centrosymmetric real matrices,

Linear Algebra and its Applications 484(2015) 356 - 378

- Catoni, Francesco and Boccaletti, Dino and Cannata, Roberto and Catoni, Vincenzo and Zampeti, Paolo, Hyperbolic Numbers. Geometry of Minkowski Space-Time Springer Berlin Heidelberg Berlin, Heidelberg, (2011) 3–23 ISBN: 978-3-642-17977-8

- Curtis, Charles W.; Reiner, Irving. Representation Theory of Finite Groups and Associative Algebras, John Wiley & Sons (Reedition2006 by AMS Bookstore), (1962) ISBN 978-0-470-18975

- James R. Weaver. Centrosymmetric (Cross-Symmetric) Matrices,Their Basic Properties, Eigenvalues, and Eigenvectors, The American Mathematical Monthly, Mathematical Association of America, (1985) 10-92, 711–717 ISSN: 00029890, 19300972 doi:10.2307/2323222

QR_decomposition_of_split_complex_matric

Copyright © 2018, Konrad Burnik

![]() such that it has an infinite metric base

such that it has an infinite metric base ![]() with the following properties:

with the following properties: is not dense;

is not dense; of

of  we have

we have  ?"

?"![]() be defined as

be defined as![]()

![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is a metric on

is a metric on ![]() , denoted by

, denoted by ![]() and

and ![]() is a metric space.

is a metric space.![]() and the integer lattice

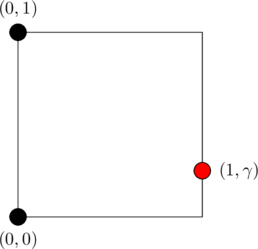

and the integer lattice ![]() as the candidate for such a set. Here I will explain why this set is a good candidate.

as the candidate for such a set. Here I will explain why this set is a good candidate.![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is a countable set, which is not dense in

is a countable set, which is not dense in ![]() which can be seen by taking for example

which can be seen by taking for example ![]() and

and ![]() then

then ![]() . By [1] the space

. By [1] the space ![]() does not have a finite metric base, therefore

does not have a finite metric base, therefore ![]() itself can not contain a finite metric base. What is left to prove is that

itself can not contain a finite metric base. What is left to prove is that ![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() . The rest of this blog post is concerned with proving this fact.

. The rest of this blog post is concerned with proving this fact.![]() such that either

such that either ![]() ,

, ![]() or

or ![]() ,

, ![]() Let

Let ![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() .

.![]() . My conjecture is that this also gives a complete characterisation of finite metric bases for

. My conjecture is that this also gives a complete characterisation of finite metric bases for ![]() however, this is a topic for another blog post. For now, it seems that the result stated in Proposition 1 coincides with some parts of results from [1] and as such will be sufficient for our needs.

however, this is a topic for another blog post. For now, it seems that the result stated in Proposition 1 coincides with some parts of results from [1] and as such will be sufficient for our needs.![]() and

and ![]() be metric spaces. If

be metric spaces. If ![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() and

and ![]() is an onto mapping such that there exists

is an onto mapping such that there exists ![]() with the property

with the property![]()

![]() , then

, then ![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() .

.![]() where

where ![]() by using the known result of Proposition 1 and finding a suitable map

by using the known result of Proposition 1 and finding a suitable map ![]() .

.![]() be a metric base for

be a metric base for ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() where

where ![]() be defined as

be defined as![]()

![]() . Then

. Then ![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() .

.![]() it is easy to verify that

it is easy to verify that ![]() defined in Proposition 3 satisfies the property of

defined in Proposition 3 satisfies the property of ![]() from Proposition 2.

from Proposition 2.![]() is indeed a metric base for

is indeed a metric base for ![]() .

.![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() .

.![]() . Let

. Let ![]() and assume that

and assume that![]()

![]() .

.![]() such that

such that ![]() and

and ![]() . Namely, we can take for example

. Namely, we can take for example ![]() such that

such that ![]() and set

and set ![]() . Now set

. Now set ![]() and

and ![]() .

.![]() are a metric base for

are a metric base for ![]() . By Proposition 3 there is a map

. By Proposition 3 there is a map ![]() such that

such that ![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , then

, then ![]() for all

for all ![]() implies

implies ![]() .

.![]() is a metric base for

is a metric base for ![]() .

.![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{bmatrix}JW & JZ \\JX & JY\\end{bmatrix} =\begin{bmatrix}YJ & XJ \\ZJ & WJ\end{bmatrix}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-dd5627f494d4bca7581085523a98716c_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[{cs}(A) = {cs}(W + jZ) = \begin{bmatrix}W & ZJ \\JZ & JWJ\end{bmatrix}= \begin{bmatrix}1 & 2 & 3 & 2 \\3 & 4 & 5 & 4 \\4 & 5 & 4 & 3 \\2 & 3 & 2 & 1\end{bmatrix}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-1c69ab9d656b5f8fe677e72f6445a893_l3.png)

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\chi_S(x) =\begin{cases} 1, & x \in S \\ 0, & x \not \in S \end{cases}\]](https://konrad.burnik.org/wordpress/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-064bd0cca97592aa71745aad2444c6ab_l3.png)